The Office Perimeter and What We Control

Many organisations feel reasonably confident about their internal network security. Within the office perimeter there is structure and visibility. Firewalls are configured, monitoring is in place, patching is managed and access is governed by an IT team that understands exactly what it owns and controls. Infrastructure is documented, maintained and subject to oversight.

Inside that environment, there is clarity.

The question is what happens when staff connect to work systems from networks your IT team does not control. Not occasionally, and not exceptionally, but as part of normal working life. Over the last decade, the way people access corporate systems has expanded well beyond the traditional office boundary, yet much of our security thinking still assumes that the network itself is trusted.

Traditional models were built around what might be called the controlled network edge: the office network, managed infrastructure, known configuration and active governance.

The Growth of the Uncontrolled Network Edge

As working patterns have evolved, so has the size of the uncontrolled network edge. This now includes home networks, serviced offices and coworking spaces, client sites, hotels and event venues, and any other environment where staff connect to work systems using infrastructure outside organisational control.

These networks are not inherently malicious and in many cases they function perfectly well. The issue is structural rather than dramatic. When connecting through an unknown network, you cannot verify the router firmware, you do not know who has administrative access, you do not know how it has been configured and you have no reliable way of knowing whether anything malicious has been introduced. There is not even certainty that the network is what it appears to be.

Even if your endpoint is well secured and your traffic is encrypted, you are still traversing infrastructure you do not control. That distinction is subtle but important.

This is one reason why agencies including the NSA and CISA in the United States, GCHQ and the NCSC in the United Kingdom, and their counterparts in Canada, Australia, Japan and the Netherlands have increasingly focused on edge devices and unmanaged infrastructure in recent guidance. The concern is not hypothetical catastrophe. It is the recognition that edge infrastructure has become a routine point of exposure in modern networks.

Why Existing Security Controls Do Not Address This Layer

A common and entirely reasonable response is that strong security controls are already in place. Many organisations deploy VPNs or zero trust architectures, implement robust endpoint protection, enforce multi-factor authentication and monitor access closely. These are important and effective measures.

However, they are designed to secure identities, devices and data flows; they do not change the integrity of the network to which a device is physically connected.

A VPN secures an encrypted tunnel, but it does not verify the firmware of the local router. Endpoint protection secures the device itself, but it does not guarantee that the surrounding infrastructure has not been compromised. Identity controls govern authentication decisions, but they do not prevent activity occurring on the same local network before traffic enters the corporate security stack.

In other words, these controls address different layers of the problem. The uncontrolled network edge sits beneath them.

“It Hasn’t Been a Problem for Us”

It is entirely possible that an organisation has not experienced a visible incident linked to external network access. That experience should not be dismissed. It may be that the risk has not materialised, that it has not been detected or attributed at the network layer, or that it has not yet resulted in measurable harm.

At the same time, the threat landscape has evolved. Automated scanning and exploitation of vulnerable edge devices now occurs at scale. Credential harvesting and probing are routine rather than targeted. Edge infrastructure is attractive to attackers not because a specific organisation has been singled out, but because automation makes opportunistic exploitation efficient. This shift in activity is precisely why security agencies have begun to highlight unmanaged network infrastructure as an area requiring attention.

Cyber incidents rarely result from a single dramatic failure. More often they resemble the Swiss cheese model of risk, where multiple defensive layers each contain small imperfections. Most of the time those imperfections do not align. Occasionally, they do.

Consider a scenario in which a home router is running outdated firmware, another device on the same network has been compromised and begins lateral probing, a work device is missing a recent patch and a local configuration is slightly more permissive than intended. None of these issues in isolation is catastrophic. Together, they can create a path that would otherwise not exist.

The uncontrolled network edge represents one of those slices that is often assumed rather than verified. Removing that assumption does not eliminate all risk, but it reduces the number of variables in play and narrows the conditions under which those imperfections can align.

When Uncontrolled Network Edge Risk Becomes Material

This does not mean that the uncontrolled network edge is the biggest cyber risk facing every organisation. For some, ransomware resilience, identity management or supply chain exposure will sit higher on the agenda. Larger organisations with significant in-house capability may have architectural approaches that mitigate this risk in other ways.

However, for many businesses, particularly those handling sensitive information or operating in markets where trust is commercially important, the uncontrolled network edge represents a structural blind spot rather than an actively managed risk. Increasingly, organisations are recognising that visible security maturity forms part of how they differentiate themselves to customers, partners and regulators.

The relevance will vary. The question is whether the exposure is understood and consciously accepted, or simply inherited by default.

A Pragmatic Structural Response

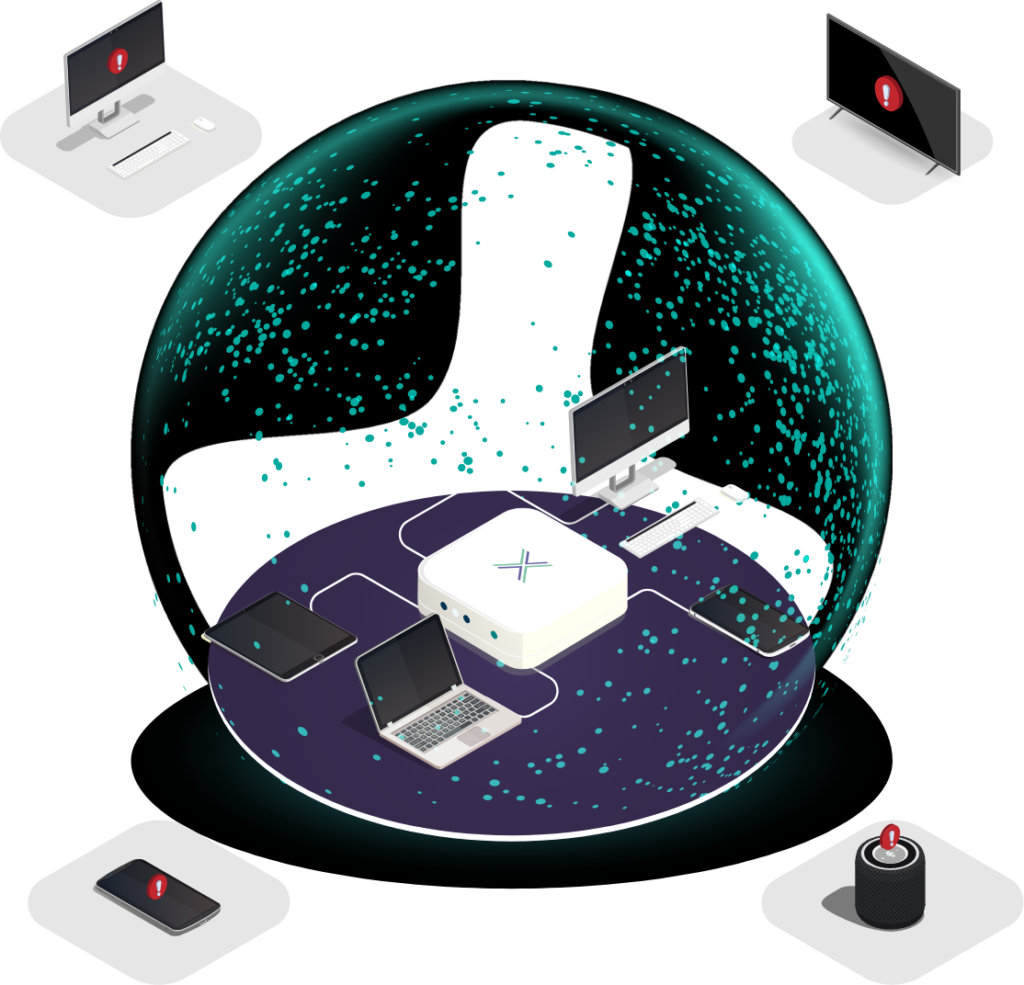

One pragmatic way to address this exposure is to create a separate, known and controlled network dedicated to work access, independent of the surrounding infrastructure. The principle is straightforward: known firmware, known configuration, automatic updates, isolation from the underlying local network and consistency regardless of location.

That is the problem Loxada was designed to solve. Loxada provides managed secure routers running proprietary secure firmware that is automatically updated and specifically designed to create a trusted work network when connecting outside the office environment. It does not replace endpoint protection, identity controls or existing VPN architectures; it complements them by restoring control at the uncontrolled network edge.

A Conscious Decision

This is not about assuming compromise everywhere. It is about recognising that as organisations extend beyond the traditional office perimeter, the definition of “your network” becomes less clear.

Some will conclude that existing controls are sufficient and that the residual exposure is acceptable. Others will decide that restoring control at the uncontrolled network edge is a proportionate and low-complexity improvement.

The important point is that the decision is conscious rather than accidental.